PDA Burnout

Understanding, Preventing, and Recovering from PDA/neurodivergent burnout.

This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org, a carbon-neutral business that financially supports independent bookstores. I earn a commission through affiliate purchases, but it won’t cost you extra!

Table of Contents

I was 15 the first time I burned out—over 20 years have passed, but some days, I feel like I'm still recovering!

Burnout is a common condition for people of all neurotypes. Most data on burnout deals with occupational burnout that results from work-related stress, and some studies suggest that more than half of American workers are currently experiencing burnout.

Even though burnout can affect people of any neurotype, PDA burnout can look different than neurotypical burnout. As an AuDHD/PDA adult, burnout can leave me unable to speak or get out of bed for weeks—and it's possible to remain in burnout for months or even years. I'm a homeschooling, work-from-home mom with a household to run—burnout can derail my entire family.

What Is Burnout?

Almost everyone instinctively understands what you mean when you say you're "burned out," but in most countries, burnout isn't a formally recognized mental health condition. Nevertheless, burnout has been a subject of well-documented psychological research for 50 years.

When was burnout first acknowledged?

Graham Greene first used the term burnout as we know it in his 1960 novel A Burnt-Out Case. Greene's story features Querry, a famous architect going through a crisis of faith after a personal tragedy. Querry is so unable to find meaning or joy in any aspect of his life that he flees to a leper colony in the Congo, where a doctor diagnoses him as the mental equivalent of a "burnt-out case," a term for a leprosy patient who the disease has physically ravaged.

In the 1970s, psychologist Herbert Freudenberger popularized the term "burnout" to explain his observations while studying helping professionals—doctors, nurses, social workers, public health employees, and teachers—who are both ideologically dedicated to their work and under extreme stress.

Freudenberger observed that burnout is characterized by physical and behavioral symptoms such as:

Fatigue

Frequent headaches

Indigestion

Difficulty sleeping

Shortness of breath

Anger

Suspicion

Overconfidence

Cynicism

Depression

Freudenberger defined three core aspects of burnout:

Profound exhaustion—especially emotional exhaustion, feeling drained, listless

Decreased personalization—feeling distant, indifferent, even cynical

Reduced feelings of personal accomplishment—low self-esteem, feeling like you're never enough, viewing your labor through a negative lens

In the late 70s and early 80s, social psychologist Christina Maslach built on Freudenberger's research, developing the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a survey to measure burnout still in use today.

Is burnout always work-related?

When people talk about burnout, they often mean occupational burnout, which is the focus of most research. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) formally recognized burnout as an "occupational syndrome." Most articles describe burnout as a "workplace phenomenon," but you don't have to be employed to experience burnout.

I burned out big time in early 2020 as a disabled, immune-compromised person homeschooling three young children during a pandemic. Burnout is a fundamental mismatch between your energy, strength, and resources and what external sources demand. Anyone under constant stress that outpaces their ability to complete their stress response cycles may eventually burn out.

What is the stress response cycle?

Science time! You encounter a stressor. Sensing a threat, your amygdala—an almond-shaped bit at the center of your brain—activates. The amygdala tells your sympathetic nervous system—the network of nerves that prepares the body’s stress response—to start pumping out adrenaline and cortisol, the stress hormones.

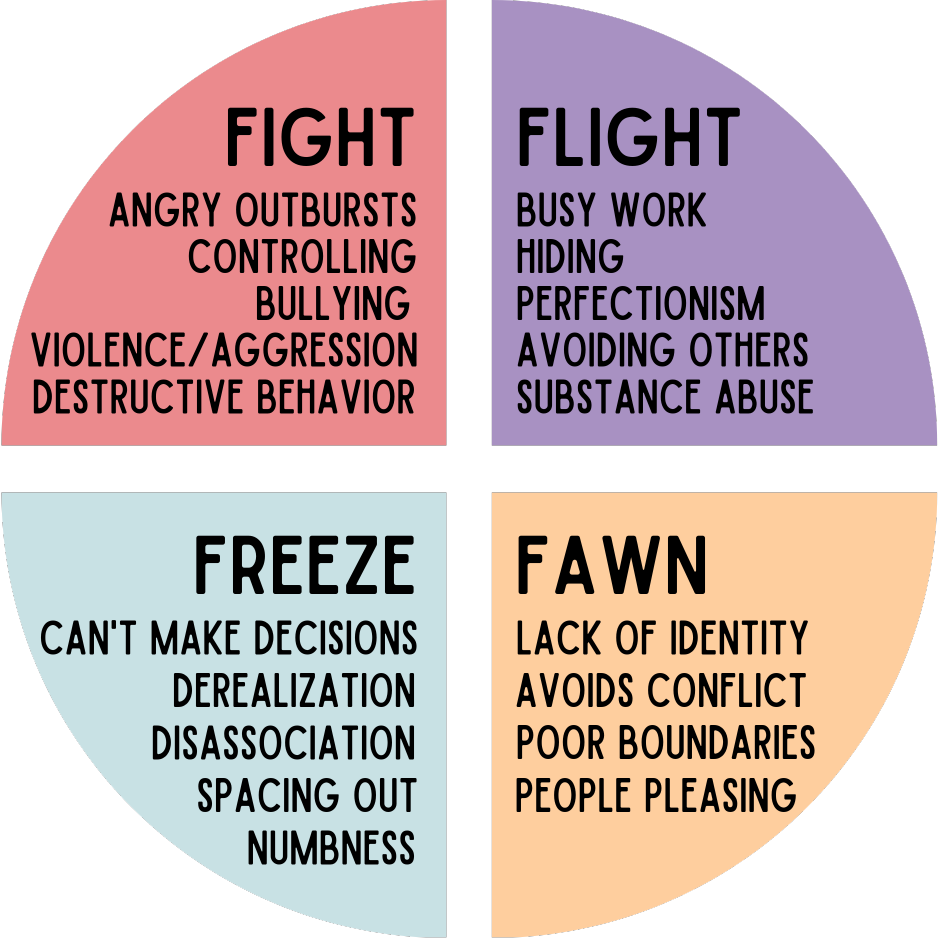

Your autonomic nervous system increases your heart rate and blood sugar levels. You breathe faster. Your brain enters stress response mode, preparing your body to fight, flee, freeze, or fawn.

This system worked well for humans when our primary stressors were things like being eaten by a bear. If you encounter a bear, your brain initiates stress response mode, giving you the energy and focus needed to survive. After you run away (or win a bear fight), your body activates the parasympathetic nervous system—your "rest and digest" mode—which slows your heart rate, lowers blood pressure and returns hormone levels to normal.

Your nervous system is ridiculously efficient at executing the stress response cycle. Your amygdala activates in response to a stressor before your brain fully processes what's happening, allowing you to instinctively avoid danger without making conscious decisions about your actions.

The problem is that modern stressors aren't (typically) things that want to eat you; they're daily chores like social obligations, reading e-mails, paying bills, meeting your family's needs, and systemic stressors like racism, misogyny, and homophobia.

Most of your stressors are chronic problems you don't resolve physically—you can't fight your e-mails—so you're not completing your stress response cycles. If you never complete your stress cycle, your parasympathetic nervous system isn't activated, and your autonomic nervous system may not return to baseline.

Is burnout dangerous?

Burnout is more than everyday stress that you can resolve with a few days off—it's a serious health concern. Burnout can:

Increase your risk of cardiovascular disease as much as smoking

Negatively impact your personal and professional relationships

In 2022, the U.S. Surgeon General listed health worker burnout as a priority after studies showed that half to three-quarters of American health workers were experiencing burnout. Burnout leads to an increased risk of mental illness, and many healthcare workers choose to leave the industry prematurely.

Understanding PDA Burnout

Experts widely view PDA as a neurological disability that causes heightened anxiety, stress reactivity, and nervous system dysregulation. I can tip into "fight, flight, freeze, or fawn" mode incredibly easily. My brain interprets any perceived loss of equality or autonomy as a life-threatening event.

I often experience a loss of autonomy as deep physical pain. Muscles naturally tighten during the stress response, and despite a high pain tolerance, this can become excruciating, which further lowers my tolerance for stress and anxiety.

Like everyone, my stress cycle activates before I can think about it, so I can't reason my way out of it. I can override my stress response for a while, but if I'm never completing my stress cycles, stress and anxiety accumulate and inevitably become unmanageable.

This unresolved stress response cycle is what can lead to a kind of "Jekyll and Hyde" presentation in PDAers. A random stressor—maybe something that seems small to observers—is the straw that breaks the camel's back, and all of the stress and anxiety I've tried to swallow bursts to the surface at once. This loss of emotional control is my body's attempt to "get to safety" and complete my stress cycle.

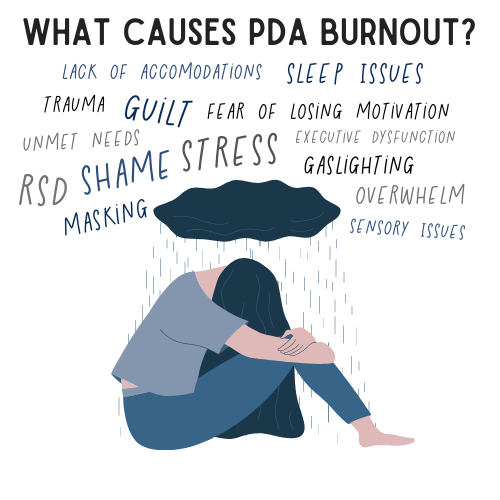

What causes PDA burnout?

I'm just like everyone else—I burn out when the stress I'm under outpaces my ability to cope with that stress—but because I'm neurodivergent, I'm expending much more energy navigating the world than neurotypical folks. Society isn't designed for brains that work like mine, so it can feel like I'm playing life on hard mode all day, every day, forever.

Many (most?) PDA people aren't getting adequate support or accommodations for their disability, and stigmas against PDA persist even within the neurodivergent/autistic community. External prejudices and internalized ableism can leave PDAers of all ages to constantly combat negative labels like:

Lazy

Defiant

Dramatic

Crazy

Rude

Manipulative

Controlling

Young PDAers are typically forced to navigate additional negative labels that society reserves for youth, like:

Brat

Bad

Naughty

Spoiled

Struggling against society's openly hostile views (and sometimes outright denial of PDA) while also unpacking internalized ableism and attempting to navigate a demanding society that refuses to accommodate our neurotype is exhausting.

The increased difficulty we face simply surviving in the world reduces our tolerance for more basic contributors to burnout. Carrying this constant mental load can mean that PDAers burn out faster under stress than the average person, and neurotypical people often overlook or underestimate our severe distress.

Sleep Issues

Sleep issues are common for neurodivergent folks. In a survey by the National Autistic Society, almost 90% of autistic respondents reported poor quality of sleep.

Sleep problems associated with autism and other forms of neurodivergence include:

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Circadian rhythm disorders, like Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder, are common in neurodivergent people. Our internal clocks are more likely to operate on a different schedule than those of most neurotypical people, and we may have extreme difficulties adhering to a conventional sleep-wake pattern.

Parasomnias

Nightmares, sleepwalking, night terrors, sleep paralysis, bedwetting, and other parasomnias—partial arousals from sleep—are more common in neurodivergent people and may affect our daytime behavior more than neurotypical people. When parasomnias lead to nighttime awakening, we often have a more difficult time falling back to sleep than neurotypical people do.

Revenge Procrastination

Navigating neurotypical society can be so overwhelming that we can dread starting a new day and, therefore, resist going to bed. At night, we (generally) have fewer obligations. We can better control our sensory environment and are free to engage in preferred activities. It can be incredibly tempting to push back bedtime when you have the opportunity to finally feel relaxed for a minute.

Hyperfocus

We might be so enthralled with our special interests that we lose track of time. Suddenly, it's 5 AM, and we haven't eaten or slept since yesterday! Hyperfocus isn't bad—it's my favorite part of being AuDHD/PDA—but when we're so absorbed in our activities that we forget to take care of ourselves, it can contribute to burnout.

Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria

Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria (RSD) commonly occurs with ADHD and autism. RSD causes intense emotional reactions to the perception of rejection from other people. PDAers can hyperfixate when analyzing our social interactions, and we often remember negative interactions longer and more intensely than positive ones.

Personally, my RSD and my demand avoidance can feed into each other and create a negative spiral. When I interpret a situation as a threat to my autonomy, I feel like the person I'm with doesn't regard me as an equal, which makes me feel rejected. My RSD causes intense physical and emotional pain and can lead to meltdowns. As a child, I would lash out aggressively—attempting to equalize a situation by hurting someone before they could (further) hurt me.

I can also do the opposite and become people-pleasing—I'll commit to things I don't have the spoons for to prove that I'm a worthy friend, family member, or coworker. No matter how well-intentioned this is, it backfires big time—if I shut down or burn out, I won't be keeping my commitments, and other people will be disappointed and hurt.

Masking

Many neurodivergent people learn to mask early—the "mask" being an outward facade that we project to try to fit in with neurotypical society. Social stigmas about neurodivergence drive masking, and it's a massive source of stress for most of us.

In research, autistic subjects report that masking makes them feel disconnected from their identity. Masking can lead to neurodivergent people suppressing their natural self-regulating methods, like fidgeting or stimming. In extreme cases, the stress of masking can lead to suicidal ideation.

Unfortunately, masking isn't something neurodivergent people can just decide to stop doing. Many of us have been so well-conditioned to mask that we have to spend a lot of time unpacking our thoughts and behaviors to develop a positive neurodivergent identity and untangle what's masking and what's not.

Masking can also be a legitimate safety issue—autistic people are more likely to be victims of violence. For example, autistic women are two to three times more likely to be victims of sexual violence than the general population, and people with disabilities, including neurodivergent people, are more likely to be subjected to excessive force—or even killed—by the police.

The devastating truth that we learn as we grow up is that we're less likely to be abused or killed if we're good at masking.

Guilt and Shame

Guilt and shame can be sources of severe stress for PDAers and lead to burnout, depression, and even self-harm or suicidal ideation.

As a child, I knew my behavior was abnormal, and the guilt and shame were unbearable. It's truly terrible to try as hard as you can and still know you're not living up to the most basic social expectations. At 13, my biggest wish was that someone would accidentally kill me during a meltdown so I wouldn't have to endure the shame.

I see a lot of parents of PDA youth who think their child doesn't experience remorse, guilt, or shame. From my experience and listening to the experiences of other PDA adults, I believe this is almost always false.

If a PDA child doesn't appear remorseful:

Their shame may be so overwhelming that they disassociate themselves

They may experience constant feelings of guilt and shame and bury these feelings to function

They find it difficult to trust other people due to a history of dismissive interactions or gaslighting

They may black out during meltdowns and don't clearly remember their behavior

What does burnout look like in PDA children?

As a child, I would melt down violently at home from the accumulated stress of masking and overriding my stress response at school, a phenomenon counselor Andrea Loewen Nair coined as after-school restraint collapse. Years of dysregulation from the lack of appropriate accommodations eventually led to burnout, and it took two years to recover.

I often see parents in PDA support groups lamenting that their once-productive child is now unwilling to do anything—I'd wager that the majority of the time, these children are burned out.

Signs of Burnout in PDA Children:

Inability to meet basic needs—restricting food intake, refusing to walk, frequent bathroom accidents, etc.

Poor sleep or a significant deviation from their standard sleep patterns

Decreased communication or selective mutism

Reduced tolerance for perceived demands

Increased need for undivided attention/extreme separation anxiety

Intense refusal to leave the house (or their room)

Increased aggression, violence, self-harm

Memory problems, gaps, or loss

Feeling disconnected from themselves or others

Feeling like most things are a demand

Feeling like the word is unreal or dreamlike

Can you prevent PDA burnout?

Knowing how to recover from burnout is essential (and we'll get to that shortly!), but the best way to deal with burnout is never to get burned out in the first place. But is it realistic for neurodivergent folks to avoid burnout? Yes! You can reduce your risk of burnout if you have the knowledge and skills.

Honestly? I don't know if I'll ever be practiced enough at these skills to prevent burnout entirely. Still, given how devastating it can be to my life (and, you know, how incredibly unpleasant it is to burn out), it's worth the attempt.

Listen to Your Body

OK, yeah, I laughed the first time I read this advice. Listen to my body? I have no interception—the sense that helps you feel what's happening inside your body—at ALL. I passed out on the floor before realizing I was thirsty multiple times.

I'm still not very good at this, but I have seen slight improvements, and mindfulness has helped me the most.

Neurodivergent Mindfulness

Many neurodivergent folks are resistant to mindfulness—probably because we get asked if we've tried to "cure" ourselves with yoga six times a week, and the idea of silent meditation with our thoughts running wild is legitimately terrifying.

Fortunately, mindfulness doesn't have to be a two-week silent meditation retreat. Mindfulness can be a walk in nature where you listen to the sounds around you, a two-minute guided meditation, or devoting all your attention to a sensory experience.

I've been practicing meditation daily for a few years now, and I'm learning to check in with my body when I first notice that I feel like dirt instead of pushing that feeling to the back of my mind. A quick body scan meditation can be perfect for this, but anything cultivating your ability to pay attention at the moment will help build this skill.

I listen to guided meditations on a mindfulness app almost every night. This routine helps me fall asleep and dedicates a regular time of day to practice that doesn't feel like it's getting in the way of other things. This routine really helped my oldest neurodivergent child tune in to her body and emotions. She has emotional awareness skills that I only started learning in my 20s!

Rest Intentionally

Autistic people often have difficulty transitioning from one state to another and sometimes describe our activity patterns as "living in extremes." When we're absorbed in a project, we tend to be ALL IN—blinders on, no concept of time, and generally get a bit obsessive about whatever we're engaged in. When we have these more functional, productive moments, we can resist intentional rest and downtime.

I tend to have extreme anxiety over consciously stopping a productive workflow. I often feel like I'm playing catch-up with my neurotypical peers and can't afford to take time off because I'm "behind" some arbitrary benchmark.

Sometimes, it feels like the only way to make any progress as a neurodivergent person is to try to actively juggle everything constantly by any means necessary. I've fallen out of hundreds of routines and abandoned so many projects that I can start to feel like if I drop any ball, I'll drop all the balls and never manage to pick them back up again.

I'm also keenly aware that it can be highly challenging to transition from a resting state into an active state to get started on a task or project again. The pressure to engage in multiple transitions from work to not-work to work again can significantly add to my stress load.

While neurotypical people do best taking small breaks, I work better when I roll with my natural inclinations. I work hard and rest hard. Taking a 20-minute break backfires because it's not enough time to recharge meaningfully, and it disrupts my flow. Taking full days off works much better for me than squeezing rest breaks into the middle of a project.

From experience, if you don't deliberately take time off, your body will force the issue. In my early 20s, I worked full-time at a grocery co-op, hauling 50-pound produce boxes while attending community college. Almost every time I had a day off, I would get sick—usually a debilitating migraine—and wind up in bed the entire time.

This was life for two years. I never had an actual day off, which was a ticking time bomb for burnout. Burning out was awful, but my body forced me to rest because I wasn't resting by choice.

Do Something

When you think about rest, you probably think about vegging out in front of the TV or scrolling through your phone. That's not bad—we all need to dial our bodies and brains down occasionally, but it's not always nurturing.

I'd consider lots of my screen time high-quality rest and engagement, but I'm also guilty of scrolling Reddit for hours without realizing what I'm doing. I'm not enjoying myself, recovering, or replenishing my energy—I'm just stuck, and I often feel worse afterward than when I started.

I recognize that binge-watching TV shows I don't care about until I'm so tired that I'm nauseated is not self-care, but I don't always put that knowledge into practice. I've never been good at maintaining what I call "work hobbies," like gardening, sewing, hiking, etc.

One of the best things I've done is dig into why I like TV, movies, and video games and lean into that in other ways. I LOVE narrative, characters, story analysis, and word building, so some activities that work well for me are:

Playing tabletop role-playing games

Writing fiction

Analyzing movies with my partner

Drawing

Burnout expert Amelia Nagoski, who co-authored the incredible book Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle offers this simple advice:

In her video "burnout expert's best advice (that sounds like the worst advice) for managing stress," she suggests (and I'm paraphrasing) doing anything you can do with your body that gives you a sense of accomplishment—gardening, organizing, making something, singing a song—anything that's not nothing!

If you're a parent of PDA kids, I am not saying you should restrict screen time. I generally advise unlimited screen time and allow unlimited screen time for all of my kids.

Instead, encourage your kids to think about how they spend their downtime. Is the activity they're engaged in refreshing, or is it making their bodies feel worse? Are they getting a sense of accomplishment from a video game they love, or are they stuck on something that doesn't mean anything to them?

Get Enough Sleep

Most adult humans need around seven to nine hours of sleep every night. I'm sure you know that sleep is essential, but more than a third of American adults are sleep-deprived. Your stats are even worse if you're an adolescent: over half of middle school-age kids and 2/3 of high school-age teens don't get enough sleep.

We already discussed the fact that neurodivergent people are more likely to have sleep issues than neurotypical people, so how are you supposed to get enough sleep when you're predisposed to sleep problems?

Neurodivergent Sleep Tips

I won't get into all the oft-repeated sleep advice you've probably already heard—cut out screens, make your room pitch-black, develop a bedtime routine. Many of these tips don't work for neurodivergent people; if they work for you, you've probably already figured that out.

Instead, here are some lesser-known sleep tips and atypical advice for folks who aren't helped by the common sleep talking points:

Lower your body temperature. Most sleep experts suggest keeping your bedroom cool. Some people can "trick" your body into feeling sleepier by taking a hot shower or bath an hour or so before bed. Your body cools off rapidly when you get out of the water, and this temperature drop can signal to your body that it's time for sleep.

Take melatonin an hour to 90 minutes before you want to be asleep. This gives it time to "kick in," so you're not lying in bed stressing about not falling asleep.

Use dim red lights (yellow and orange also work if you don't like red - not quite as good, but they're still good!) in your bedroom at night to reduce your exposure to blue light.

Try acupressure for sleep. Talk to a doctor before trying acupressure if you're pregnant, think you could be pregnant, or have wounds, numbness, swelling, infection, or recent blood clots in the areas where the acupressure points are. If you experience dizziness, discomfort, or anything that doesn't feel "right" to you, stop immediately and talk to a doctor! You can also lay on acupressure mats before bedtime. I have a neck pillow acupressure mat that looks like a torture device, but I love it.

Don't be afraid to experiment. I fall asleep best with a TV in my bedroom turned on—the opposite of mainstream sleep advice. I turn on "comfort shows," which I've seen many times before, so I don't need to pay close attention.

Set Boundaries

Both PDAers and parents of PDA kids can get confused about boundaries. Boundaries are about you—the management of your internal and external resources.

PDA folks may try to control other people in their attempts to lower anxiety, and PDA parents try to control PDA children to maintain a hierarchy. Both situations are pretty unhealthy and have nothing to do with boundaries. Many posts asking about boundaries in PDA support groups are really asking: How can I control someone else's behavior?

You can't set boundaries to control other people. The only person you can control is yourself.

PDAers often have difficulty setting healthy boundaries. People pleasing isn't a trait that most people associate with PDA, but it's common for masking or internalized PDAers to engage in fawning—extreme people pleasing and conflict avoidance.

As neurodivergent people, we're often afraid that we'll lose the people we care about if we're not accommodating. We may have internalized messages about laziness or unreliability and feel we must constantly take on more (and more and more...) to prove our worth.

In the long term, setting healthy boundaries helps you nurture yourself and your relationships. Setting healthy boundaries means:

You don't resent people because your outside voice said yes when your inside voice screamed NO. Holding boundaries creates emotional bandwidth for compassion and empathy.

You can meet your needs, which gives you more energy to be a better friend, spouse, parent, coworker, student, etc., and fully engage with the things you choose to say yes to.

The people in your life see that you trust them enough to be honest, which can strengthen the relationship. Being "nice" and being authentically loving are entirely different things.

How to Set Healthy Boundaries

No is a complete sentence; you don't owe anyone an explanation for saying no.

However, if you're used to people-pleasing, it may be easier if you use mild language like I'd love to help you with X, but I've decided not to do that anymore for my mental health.

I love the Gottman Institute phrase: protect my peace. I'm sorry, I'd love to help, but I need to protect my peace right now. This phrasing lets people know it's not about them— you're guarding your sense of safety and calm.

People might get mad when you start setting boundaries. That's OK. Change can create anxiety. You are not responsible for their reaction. Over time, your relationship can grow into a healthier, more respectful place.

If they stay angry long-term, remind yourself that you deserve to be surrounded by people who care about you, not just what you can do for them. Jessica McCabe of How to ADHD recommends tuning in to how your body feels when someone asks something of you (or when you engage in a specific behavior/activity). Do you feel anxious? Angry? Resentful? That may be an excellent place to set a boundary.

When considering how to set boundaries, Brene Brown asked herself,

"What boundaries need to be in place for me to stay in my integrity and make the most generous assumptions about you?"

Your mileage may vary, but I found that quote really powerful. Some helpful questions I asked myself are:

What boundaries do I need to stay in my integrity?

What do I need in place to be authentically myself, to respect the limits of my energy, money, and time?

What boundaries do I need to make the most generous assumptions about other people without viewing them through a lens of resentment?

Embrace Neurodivergence

I know many neurodivergent adults who have spent years wishing they would wake up neurotypical.

Do you have a fantasy version of yourself that effortlessly pays all your bills on time, has a sparkling clean house, and never loses your keys? I've been guilty of refusing to recognize or accept how my brain works, hoping my fantasy self would emerge and take over all my responsibilities.

I think everyone—neurodivergent and neurotypical—fantasizes about "fixing" parts of themselves they view as less than ideal. However, it can be really harmful to neurodivergent people if we start to view our fantasy selves as morally superior to our actual selves. This line of thought can lead us to reject support, accommodations, and systems that would help us because we're angry at or ashamed of our needs.

Lyric Rivera from Neurodivergent Rebel talks about embracing their autistic mind in their video, "How Autistic and Neurodivergent Masking and Burnout Can Become a Perpetual Cycle," saying:

“Now I know that my pace shouldn't be the same as the NeuroTypical pace. I have to modify that pace, and be more compassionate to myself. I'm not a machine. I'm not a product. I am a human, and I have human needs...Taking care of myself, because I'm NeuroDivergent, looks different than taking care of myself, when I thought I was NeuroTypical. That's a very different experience of self-care.”

To properly care for ourselves, we must embrace that neurodivergent needs differ from neurotypical ones. It's OK if your version of self and community care looks different.

How Can You Recover from PDA Burnout?

Burnout can feel like a massive trap for neurodivergent folks. The things we need to support our recovery require executive function, but we have impaired executive function on our best days—and if we're burned out, it's probably gone.

If you're a parent or caregiver for a PDA child, you're likely their primary support when dealing with burnout. Your PDAer is likely to have very high support needs while recovering and may need help with things they could previously do independently.

How can you support your PDA child’s burnout recovery?

Many caregivers feel intense internal or social pressure to push their PDA children to achieve more, but healing requires rest and support and happens in its own time. You can't make your child recover faster from nervous system exhaustion any more than you could push a child to recover faster from a broken leg.

Lower Demands

A lower-demand lifestyle benefits all PDA youth, but it's especially essential when recovering from burnout. Lower demands for your PDA child in recovery to the safest extent possible. Lowering demands might look like:

Taking time off of school

Lowering standards around personal hygiene and "getting ready"

Eliminating or reducing outings like errands, appointments, etc.

Eliminating household chores

Allowing comfort foods and free choice of where to eat

Reducing demands around manners and social expectations

Providing as much free time as possible

This might seem like letting your child run feral, but the goal is to reduce stress and anxiety to support recovery. Your child's nervous system can't support baseline functioning right now. As they recover from burnout, they'll be able to cope with more normal activities.

Consider Sensory Needs

Depending on whether your child is sensory-seeking or avoidant, they may need more or less sensory input while recovering from burnout. Many people need both—reductions in some kinds of sensory stimuli and increases in others.

Ideas for sensory-seeking children:

Active play: a climbing wall, trampoline, yoga ball, sensory swing, tunnels

Sensory bins with a variety of textures and tools

Playdough, slime, or oobleck

Water play: a water table, various bath toys, a backyard pool, time at a beach

Obstacle courses

Messy nature play: a mud kitchen, digging for worms, gardening, creek-stomping

Music and noise-making (you may want some ear defenders for yourself!)

Chewable jewelry or bubble gum

Foods with strong or unique tastes and textures: Pop Rocks, salt and vinegar chips, frozen grapes (note: grapes are a choking hazard for young children), raw apples, taffy, ginger candies, curries

Ideas for sensory-avoidant children:

Declutter the environment and try to create as much visual simplicity as possible

White noise, peaceful nature sounds, providing your child with ear defenders

Low, peaceful lighting

Soft loungewear without tags or raised seams

Safe foods that your child has already tried and enjoyed

Avoid physical touch or close contact without prior permission (this is an essential lesson in consent for any child, but especially important for the wellbeing of sensory-avoidant kids)

Comfortable items relaxing like bean bags, soft throw blankets, and stuffed animals

Deep pressure: body socks, compression vests, weighted blankets

Encourage Special Interests

Special interests (or hyper-fixations) are life-giving for autistic/PDA folks, and up to 95% of us have them. Engaging with special interests is joyful, inspiring, and soothing. Our special interests help us reach a flow state, regulate our emotions, learn new skills, and increase our sense of achievement, confidence, and self-esteem.

Your autistic/PDA child's special interests are likely extremely important and meaningful to them. Respecting your child's special interests is a huge part of building a trusting relationship.

Autistic special interests are not hobbies. Hobbies can be set aside when life gets demanding and other tasks must take priority. Special interests are essential to the wellbeing of autistics. They can not, and should not, be de-prioritized, especially when an autistic/PDA person is already burned out or facing high stress.

Having quality time to engage with my special interests keeps us functional. When burned out, our special interests can be a safe place to recover our energy and enthusiasm for life.

You can show your child you value their special interests by:

Getting curious, even if you don't share their interest—ask questions and let your child enjoy being the expert

Providing special-interest-related materials—library books, websites, YouTube videos, costumes, room decor

Avoid interrupting your child when they're deeply engaged unless absolutely necessary

Give lots of notice if they'll need to transition away from their special interest

Assist them with care needs when they're hyperfocused—quietly bring them drinks/snacks/meals, gently remind them to think about using the restroom, etc.

Suggest (but don't force) memorable experiences related to your child's interest

Special interests should never be mocked or used as a punishment or reward. Doing so will almost certainly damage your relationship with your child.

What activities support burnout recovery?

Journaling & Workbooks

Research shows that journaling can help reduce stress and anxiety, improve mental state and mood, understand feelings, and improve physical health.

Workbooks, like journals, encourage expressive writing but come with clear instructions and writing prompts. Many stress management workbooks are available in digital or paper formats.

I like workbooks because I don't have to decide what to write when overwhelmed, but some PDAers may find workbook prompts too rigid. Don't be afraid to experiment!

If you don't want to purchase a workbook but need some direction, you can use journaling prompts, which are free all over the Internet!

Playing Games

I know that meditation is helpful for me, but I struggle to keep up a meditation practice when I'm already burned out. Everything feels exhausting, and mustering the energy to press "play" on my podcast app seems like an insurmountable barrier.

Enter meditative games. I love games, so I'm more motivated to engage with them. I play games socially with my partner, which gives them an emotional connection component. Video games—often viewed as the ultimate waste of time—can induce a flow state similar to meditation.

Some of my favorite meditative games include:

Tetris (which may process trauma)

Animal Crossing

Tarot Cards

Buddha Board

Lego sets

When burned out, I tend to choose relaxing, meditative gaming experiences, but you can choose any game you enjoy. All kinds of play reduce stress, improve mental and emotional state, improve brain function, and protect against depression.

While many still think of play as a children's activity, adult gaming and play are constantly becoming more normalized! Even neurodivergent soccer/football star David Beckham builds Lego sets to control his anxiety.

Exercising

Oof.

Motivating yourself to exercise can be challenging if you're not a natural workout person. Still, it does help—there's loads of evidence that exercise reduces stress and improves mental health. Exercise is a healthy way to raise dopamine levels and enhance executive function.

If you're not already exercising, it's OK. It's challenging to start a new habit, and this is a common struggle. More than 60% of American adults don't get enough exercise, and 25% don't do any physical activity at all. You're not alone!

If you have a friend who works out, consider asking them if they'd buddy up with you to help motivate you to take walks or go to the gym.

James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits, suggests developing automatic rituals by habit stacking—combining exercise with a habit you already do. For example, you could resolve to walk around the block after you check the mailbox.

Temptation bundling—pairing a pleasurable activity with a difficult one—can help form positive associations with the habit you want to develop. For example, you can choose a TV show you only watch while walking on the treadmill.

Asking for Outside Support

Support is crucial to healing from burnout. If you're an adult caring for a PDAer in burnout recovery, proper support can keep you from becoming burned out yourself!

Proper support can be professional—like a therapist, counselor, or coach—or personal, like a friend or family member. Ideally, you'll have both!

Professionals can teach techniques for burnout recovery, provide accountability, and help you realistically assess your progress. Friends and loved ones can provide material support while encouraging activities that give you a sense of accomplishment.

Maybe a friend comes over and cooks dinner with you—some work is taken off your plate, you both get a human connection, and there's food at the end! Maybe you and your partner play a game together after the kids go to bed.

It doesn't have to be a big production. The important thing is spending quality time with someone who cares about your wellbeing.

Amelia Nagoski sums it up well when she says,

“Reach out for help because, in the end, the cure for burnout is not self-care; it's all of us caring for each other."

About NeuroNesting:

I’m an AuDHD/PDA adult, freelance writer, wife to an autistic partner, and homeschooling mom of three neurodivergent kids. I created NeuroNesting to encourage a dialogue between PDA adults and parents of PDA children—or anyone looking for a deeper understanding of PDA. Have questions, comments, or topics you’d like to see addressed? Drop me a line at ariel@neuronesting.com

I’m committed to keeping NeuroNesting free and accessible for all. If you want to support this effort financially (each post takes hours to write!) you can:

Pledge your support with a paid Substack subscription—click here to support NeuroNesting for less than $2 a month!

Purchase books at the NeuroNesting Bookshop

Wow this is epic! Thanks! I’m going to save it and read it properly from a laptop rather than a phone

This is so incredibly informative. I truly believe my 8 yr old in in burnout, however the lack of understanding of PDA makes it difficult to get others to see the benefit of low demand. Thank you for sharing your experience!